Computer Science Across the Curriculum

1. Introduction, Computer Science for Fun, and Turtling

1.1 Fun and Learning, for Students and Teachers

This booklet is the outcome of a joint venture between cs4fn, based at Queen Mary University of London (www.cs4fn.org), and the Turtle project hosted in the Faculties of Philosophy and Computer Science at the University of Oxford (www.turtle.ox.ac.uk), with support also from Hertford College, Oxford. The booklet has been co-funded by the UK Department for Education, to whom we are all extremely grateful for being able to provide it free of charge to all UK state secondary schools.

The main aim of this booklet is to provide a bridge from ideas like those explored in the cs4fn magazines – fascinating applications of Computer Science presented without much complication or technical detail – to real implementation and practical application of programs that illustrate those ideas. We hope that keen students who found these sorts of things interesting when reading about them will be motivated to explore them much more deeply, through understanding (and later building on) the programs introduced and explained here. The appendix gives lots of references to the cs4fn website, so you can trace connections both ways.

We also hope that teachers across the curriculum will find plenty here that can be used to enliven their lessons and provide ways of helping to explain some interesting phenomena – from the motion of projectiles and rockets, to evolution and the spread of diseases, to economic and social behaviour – and also to explore more speculative ideas (such as machine intelligence). Teachers, like students, can gain hugely from learning to understand and write computer programs for themselves, and little prior expertise is expected here.

This booklet does not itself aspire to teach you how to program, but there are lots of self-teaching materials on the Turtle website that will help you do just that. Once you are familiar with the rudiments of programming, we hope that you will be able to use these ideas to discover a stimulating springboard into fascinating applications that might otherwise have seemed daunting.

1.2 Introducing the Turtle System

The Turtle System (or just Turtle for short) is a programming environment designed for ease of use and learning, building in three programming languages (with Turtle Java soon to be added too):

- Turtle BASIC

- Turtle Pascal

- Turtle Python

All of these are simplified versions of standard languages, which make it easy to get started and also enable Turtle to provide lots of help for beginners. For example, the error messages can be very precise and straightforward – enabling most problems to be sorted by the student without further help – because the languages are relatively simple. Another virtue of this simplicity is to enable straightforward comparison of the different languages (for example, by swapping between the example programs and seeing how they change between the languages). This helps to demonstrate that programming in any language of this general type is essentially similar: what matters most is not the detailed “syntax” of the specific language, but rather the logic of the algorithms (i.e. the computational recipes) that the language expresses. So it really doesn’t matter what programming language you start with: once you have developed the skill of thinking algorithmically, that skill can easily be transferred to another language.

1.3 Downloading and Configuration

Turtle can be downloaded free of charge from www.turtle.ox.ac.uk, and the main system consists of one executable program – named TurtleSystem.exe – which can be run from any folder on a PC (versions for Mac and Linux are under development as this booklet goes to press). No further installation is necessary, and the system will never make any secret changes to your computer setup. Configuration of the system (e.g. so that it starts in a particular programming language, with certain options showing, or a particular menu of example programs available) is achieved by using the program menus to put it into the desired state, and then saving a Default.tgo file to fix the corresponding default “turtle graphics options”. Full details of all this – which are likely to be of particular interest to teachers – are available in the Teachers’ Guide on the Turtle website.

1.4 Seymour Papert’s “Turtle Graphics”

The name of the Turtle System is derived from Seymour Papert’s invention of “turtle graphics” as a brilliant way to introduce programming to children (of all ages!). Although originally associated with his programming language LOGO, this has proved so successful and popular that most standard languages now have at least one turtle graphics module available for learners (and often there are numerous versions, produced all over the world). The idea is to imagine an invisible turtle (though children’s systems will usually provide a visible image) who starts off pointing “north” in the middle of a drawing “canvas”, and is given drawing instructions by the written program. The first example in the Turtle System – no matter what language is chosen – gives the following instructions. (Note however that only Python will show them just like this. In BASIC, the words will be capitalised, while in Pascal, most lines will end with a semicolon. These little details can be ignored for the moment.)

colour(green)

blot(100)

pause(1000)

colour(red)

forward(450)

pause(1000)

right(90)

thickness(9)

colour(blue)

pause(1000)

forward(300)

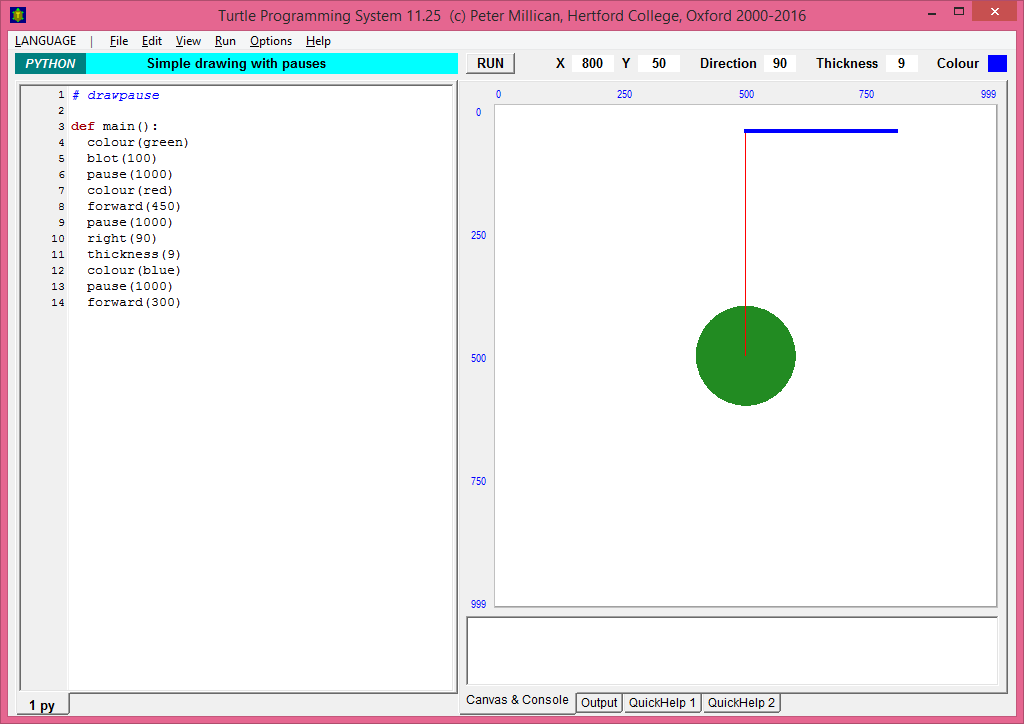

The easiest way to understand this is to run the program and see the turtle doing its work. You can run in online here: Simple drawing with pauses. The program has three pause(1000) instructions – pausing for 1000 milliseconds (i.e. one second) each time – so you can see its progress in steps. By the first pause, the turtle has drawn a green blot (i.e. a filled green circle) of radius 100 in its original position at the centre of the canvas. By the second pause, it has changed its pen colour to red and drawn a thin red line northwards, nearly reaching the top of the canvas (1000×1000 units by default, so going north 450 units leaves the turtle 50 units from the top). Then it turns right by 90 degrees, changes its pen thickness to 9 (from the default of 2) and its pen colour to blue, pauses a third time, and finally draws a thick blue line 300 units long (pointing now towards the east, after its 90 degree turn).

Note that between the second and third pauses, the canvas itself doesn’t change at all, but you can see the changes in the turtle’s direction, pen thickness and colour in the information boxes above the canvas. The values in these boxes can be used in your programs, using the names:

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

turtx | the current x-coordinate of the turtle |

turty | the current y-coordinate of the turtle |

turtd | the current direction of the turtle (expressed in degrees, by default) |

turtt | the current thickness of the turtle’s pen |

turtc | the current colour of the turtle’s pen (expressed as an “RGB” colour code) |

(In BASIC, however, these names have to be in capitals and followed by % to signify that they are integer variables, e.g. TURTX% or TURTD%.)

1.5 Moving into Computer Science

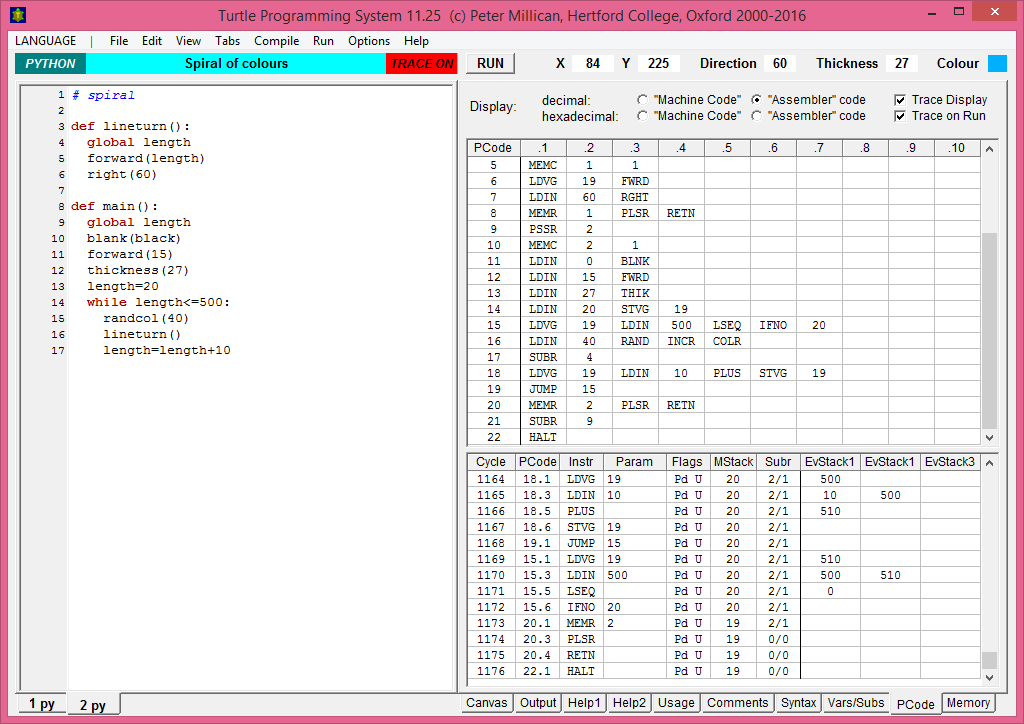

The Turtle System provides a route for students of programming to move easily into deeper aspects of Computer Science. When any Turtle program is run, it is compiled (i.e. translated) into a form of machine code called PCode, and this code is then executed on a virtual Turtle machine. (The Turtle machine is “virtual” because it is simulated in software rather than being a hardware component of your computer; so whatever happens on this virtual machine – even if it is “hacked” by one of the programs executed on it – will leave your own computer hardware completely safe.) Moreover the Turtle System makes it very easy to inspect both the machine code and its detailed processing. If you go to the View menu and select “Display Power User Menu”, you will see six new tabs appearing at the bottom right of the Turtle window, including “Usage” (which indexes the various commands used), and “Syntax” (which shows how the program has been analysed during compilation). To understand machine code, however, the most important are the “PCode” tab, which shows the machine code itself, and the “Memory” tab, which enables the machine’s memory to be examined. In the picture below, the “PCode” tab is shown, including the “Trace” display showing the execution of the last few instructions in the Python Spiral of colours example program.

For the purposes of this booklet, you don’t need to know anything about these further facilities. But they do explain some aspects of the Turtle System, in particular why its language implementations are all fully compiled (which results in some non-standard features), and – most importantly for what follows – why it natively handles numbers only in the form of integers. To process decimal numbers, therefore, it treats them as fractions (e.g. 3.1416 is treated as 31416/10000). This is quite straightforward, and best explained by illustration. So let’s now get on with seeing some real practical examples of Computer Science across the Curriculum!